What bacteria taught me about metaphysics

Seeing | Biology

![]() Hans Busstra, MA | 2024-12-14

Hans Busstra, MA | 2024-12-14

Documentary filmmaker Hans Busstra shares with us, with the aid of amazing and scientifically accurate animations of the molecular world, the background story of his journey from imaging the hardcore science of molecular biology to the fundamental insights of metaphysics.

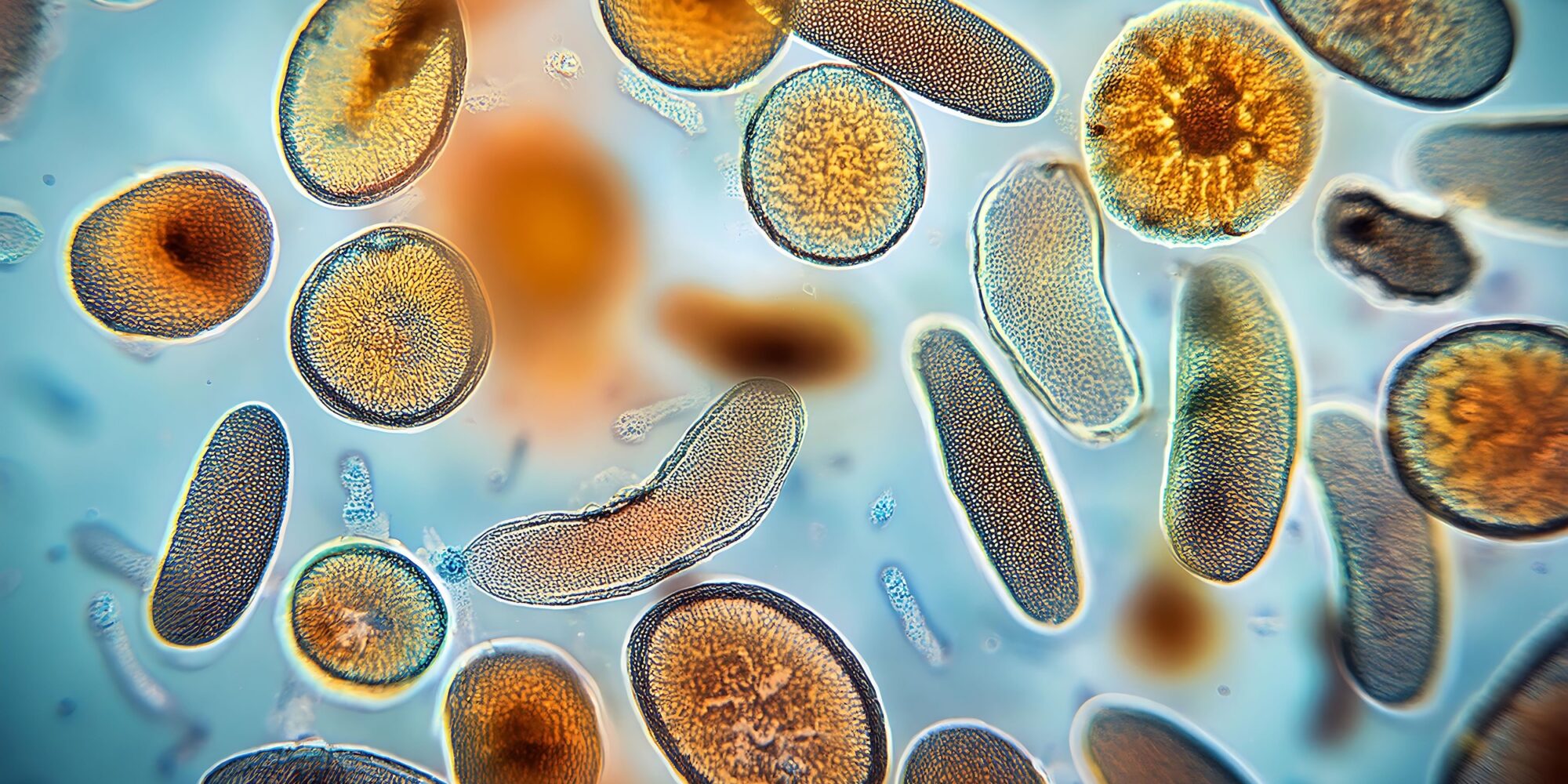

Before I had joined the Essentia Foundation, my latest documentary film project was a commissioned film about bacteria. A company that specializes in probiotics had asked me to make a scientific documentary that shouldn’t be about branding their product, but just about creating awareness about the pivotal role bacteria play on our planet. I took the assignment and dove into the microcosmos.

As I lived near Delft in The Netherlands at that time, it was only half an hour drive to the exact spot where Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, one of the discoverers of the first microscope, had first seen bacteria through his small lens in 1676. Photography was not around, so he had to convince members of the Royal Society in London with numerous letters describing how exactly he managed to see ‘invisible’ creatures in water.

I met micro-photographer Wim van Egmond—an absolute pioneer in the field of photographing and filming bacteria—who is in possession of an exact replica of Van Leeuwenhoek’s first microscope. I asked him if we could film bacteria through that lens, to re-enact more or less exactly what Van Leeuwenhoek had seen: how ‘dead’ water suddenly comes alive if you magnify it 200 times optically.

I got a tiny sense of what scientific breakthroughs must feel like to the geniuses that make them: to see the previously unseen, know the previously unknown is a deeply ecstatic experience. For instance, to see a timelapse of cyano-bacteria producing oxygen—a process that 2 billion years ago caused ‘The Great Oxidation Event’ transforming the Earth’s atmosphere and making it ready for complex life—gives a sense of being present at the origin of life.

Though we tend to forget it, science and metaphysics go hand in hand. What I find an intriguing fact is that, more or less at the same time that Van Leeuwehoek was building microscopes and discovering bacteria, a famous thinker, residing only 60 kilometers north, in an Amsterdam Canal House, was bowing his head on the mind-body problem. How does mind, consciousness, relate to the material world we perceive?

This philosopher was called René Descartes and he would install ‘dualism’ in the Western mind. Applied to bacteria: what was the reality status of Van Leeuwenhoek’s discovery, those tiny building blocks of life, which in the end were not perceived through a lens, but ‘through’ consciousness—which we, in turn, don’t understand? Now, I’m not a philosopher but a filmmaker. To my knowledge, there are no records of Van Leeuwenhoek and Descartes ever exchanging ideas. But the link I see between them is that Descartes’ division of mind and matter would enable the Western mind to get lost in the microscope.

Microbiology, chemistry and medicine don’t benefit from casting metaphysical doubt on microscopic images; it’s much more functional to regard what is being perceived as fundamental. Cells exist and by understanding them we can cure people. In other words: suspending metaphysics can be very functional.

In the documentary I was making about bacteria, I wanted to portray them in a new way. The problem is that the scale of individual bacteria borders on the wavelength of visible light. Microscopy can beautifully show biofilms and collectives of bacteria, but if you really want to further zoom in, different techniques are necessary. Scanning Electron Microscopy is one of them. By firing electrons at a sample of bacteria an image can be created that easily gets a 100 times more magnified than the strongest light-based microscopes. In the documentary, we did that with a Lactobacillus bacterium, the one present in dairy products. Though much more magnified than other images I had seen, a SEM image of a Lactobacillus is still rather boring: you see what looks like a large grain of grey rice. That’s it.

Luckily, I came across a company called Digizyme, which had previously made one of the world’s first molecular animations of the inside of an Eukaryotic cell. This animation, which went viral, was created with software that used accurate biological structure data to render 3D images of proteins. I asked Digizyme if they could render moving images of the inside of a bacterium for me, not knowing what that question would get me into.

A Lactobacillus bacterium has around three million molecules inside it, largely consisting of proteins, and each one of them meets all other molecules once a second: nine trillion molecular interactions every second. It didn’t take me long to understand what no biology textbook tells you, because it’s not relevant information: that all the nice images you see of proteins are shot with a ‘shutter speed’ of around 1 millionth to 1 billionth of a second. At that speed you cannot see anything happening at the molecular level.

So what I asked Digizyme was not only to render a cross-section of 3 million molecules, but also to slow them down a billion-fold. Molecular Maya, the software that builds these images, in the end doesn’t find it so hard to render them. The hard work is mainly in putting in the right bio-data and in making the design choices. For instance: if you were to stick a nano-camera in an accurate model of a cell, your ‘lens’ would be completely covered by molecules. So we artificially left out 2,9 million proteins and rendered a cross section of a bacterium with 150 thousand proteins. All on the nanosecond timescale.

When I got the first 3D renders coming in from Digizyme, and started editing with them, I had an ecstatic feeling of experiencing truth. We had made one of the world’s first scientifically accurate moving animations of the inside of a single bacterium, a moving image of the mechanics that underlie all life. In my choices of music I usually try to be frugal with using masterpieces, but to underscore these images it felt completely appropriate to use Bach’s Prelude in C Major (BWV 846).

When we first screened the documentary in full 4K in a theatre, the combination of the molecular animation and Bach triggered an emotional response in many in the audience. When asked, people said that it felt as though they had really seen the birth of life. In a sense they did. These animations were as scientifically accurate as we could make them, and seeing a bacterium is indeed seeing the primordial cell that has led to the Eukaryotic cells that all plants, animals and humans are made of. But what fascinates me as a storyteller and filmmaker is how small a step it is for an audience—and for me as well—to think that we actually saw a bacterium, though clearly aware of the fact that we were watching but a 3D render of the bacterium.

Cinema of course relies on this form of ‘jump,’ which filmmakers call ‘the suspension of disbelief.’ Consciously or unconsciously, we agree to get ‘carried away,’ to accept what we know to be a fiction as a fact. Bach always helps.

But when it comes to Hollywood movies, we stop suspending the disbelief the moment the lights are turned on again. We then realize that it was all a fiction, and that we weren’t really witnessing a murder mystery, but paid ten bucks to watch great actors play a murder mystery on a screen.

Now, it feels tricky to compare science to Hollywood; fantasy and fact are not the same.

But metaphysically there is a similarity: science gives us accurate, high resolution images of reality that help us make sense of the world, and those images suspend our disbelief. We get carried away, thinking that science shows us the world as it is. Yet, also in science, the most accurate models and images are but maps of reality, not the territory.

To understand and accept this with regards to a 3D model is of course not so hard: the construction of it is obvious. Much tougher to swallow for the Western mind, is the idea that also Van Leeuwenhoek’s observation, empirically verified worldwide, was still just a model.

We are just so familiar with models based on photons hitting our retina and being processed by our brains that here we start suspending our disbelief around the age of two.

Yet somehow my journey into the microcosmos kicked me back. I found myself in the back of a theatre, entertaining an audience with a nice documentary about bacteria that I was proud of. But I could no longer suspend the disbelief: I hadn’t filmed bacteria and I wasn’t sitting in a theatre. I could no longer deny that I was trapped in images, in stories of language and mind, and instead of taking them literally, it was time to see them as symbols and to find out what they were pointing to. Even if this would be a painful exercise of not-knowing, and perhaps even doomed to fail—for if you’re trapped in a story, can you break out of it with a story?—I knew: it was time to join the Essentia Foundation full time.

Here you can watch a short video about how we managed to create images of the inside of bacterium. The full documentary, Micronauts, will premiere on our YouTube channel next week.

Essentia Foundation communicates, in an accessible but rigorous manner, the latest results in science and philosophy that point to the mental nature of reality. We are committed to strict, academic-level curation of the material we publish.

Recently published

Reading

Essays

Seeing

Videos

Let us build the future of our culture together

Essentia Foundation is a registered non-profit committed to making its content as accessible as possible. Therefore, we depend on contributions from people like you to continue to do our work. There are many ways to contribute.