The ethics of idealism

Reading | Ethics

![]() Asher Walden, PhD | 2021-09-19

Asher Walden, PhD | 2021-09-19

Research suggests that there is a neurological foundation to the experience of social connectivity, and that it is the same as the foundation of consciousness itself: synchronistic alignment appears not only within an individual brain in correlation with experience, but also between people taking part in joint tasks. This can form the basis for an objective ethics, argues Dr. Walden.

We are in the midst—arguably and hopefully—of two simultaneous paradigm shifts. The first is the result of an economic and demographic transition from a world of scarcity to one of plenty. I know that most people are accustomed to interpreting current affairs in terms of the climate crisis, continuing political instability and various other causes for despair. But there are a number of prominent voices asking us to lift our noses out of the daily news and attend to the big picture of human history. Consider: the incredible and persistent drop in violence of all kinds, world-wide, in the last several hundred years; the dramatic rise in literacy and even higher education, for boys and girls; the development of vaccines to all but eliminate early childhood mortality; and most importantly, the gradual fall in average fertility, such that the world population is projected to plateau, and then begin to fall, within another generation. I imagine that instead of building walls to keep immigrants out, rich nations will be paying foreigners to immigrate, just as a matter of economic necessity. Nationalism as we have come to know it will simply make no sense. What will be the prevailing moral and political ways of thinking in this new world?

The second paradigm shift is the movement within the natural sciences towards an Idealist metaphysical picture. I won’t rehearse the arguments or the evidence for that view here. I only want to raise this question: Assuming that we accept the truth of the mind-only doctrine, what are the specifically ethical implications? Many proponents of non-dual and Idealist philosophy—especially those who have come to the view through some kind of personal transformative experience—feel that it has profound normative impacts.1 There is a renewed and intense call for love, unity and community. But can we derive an ought from an is? Is there a necessary rational connection between metaphysical unity and social unity? If so, then the new metaphysics can truly serve as a bridge between the empirical sciences and the humanities.2 A universalist and humanistic spirituality may be possible.

Now, the philosophical tradition encompasses a number of competing theories about what morality is. Given that we all agree that things like murder and theft are unethical, why is it that we characterize them so? Is there some objective fact or quality about these actions that makes them bad? If the focus is on personality factors rather than behaviors, what is the ultimate difference between virtue and vice? Is it just a matter of what traits we—or other members of our culture—like or don’t like in others and ourselves? Or what benefits us pragmatically, or what benefits the species in an evolutionary context? And so on. Well, it turns out that analytic idealism suggests its own free-standing moral theory, one that stands alongside the traditional ones such as utilitarianism and Kantian deontology. In this essay, I would like to lay out in broad strokes what I believe that moral theory might look like.

The place to start is with reviewing what this new perspective says about what it is to be a self, what it means in relation to the social and natural worlds. The conventional view is that the self is an entity that has some kind of independent and robust existence, and consciousness is something that that self ‘has’ or does. The self is logically and ontologically prior, while consciousness is epiphenomenal. The emerging view essentially reverses that relation, with widespread consequences. It says that consciousness is the basic character or substance of the universe, while our awareness of ourselves as discrete selves is an heuristic projection of one specific cognitive apparatus, perhaps the default mode network. This is the cerebral network that seems to shut down in the midst of deep meditation and mystical experience, allowing a direct perception of broader dimensions of being consciousness, especially the depth dimension of love, insight and ultimate unity.

Whether they realize it or not, humans participate in a consciousness that is greater than their own private, internal subjectivity. The ultimate substance of that subjectivity is in fact the world itself, and to the extent that we isolate ourselves from that greater world, we feel alienated, constrained, powerless and hopeless. Truly, the mystery is why we work so hard to maintain that illusion of isolation. The religious traditions have their distinctive ways of talking about that mistake: ignorance, the Veil of Maya, sin. What is clear is that it is both pervasive and strangely attractive. There are reasons why we cling to our error. But there are also good reasons why we seek to know the truth. Principally, the effort to rejoin or realign our own awareness with ‘that which is greater than ourselves’ is widely recognized as the main source of joy and fulfilment in our lives. This pleasure is the experiential side of what, from a practical side, is called morality. The concept of morality is best understood as the set of rules, behaviors and social practices which, individually and in tandem, serve to orient humans toward, and reunite us with, this greater consciousness.

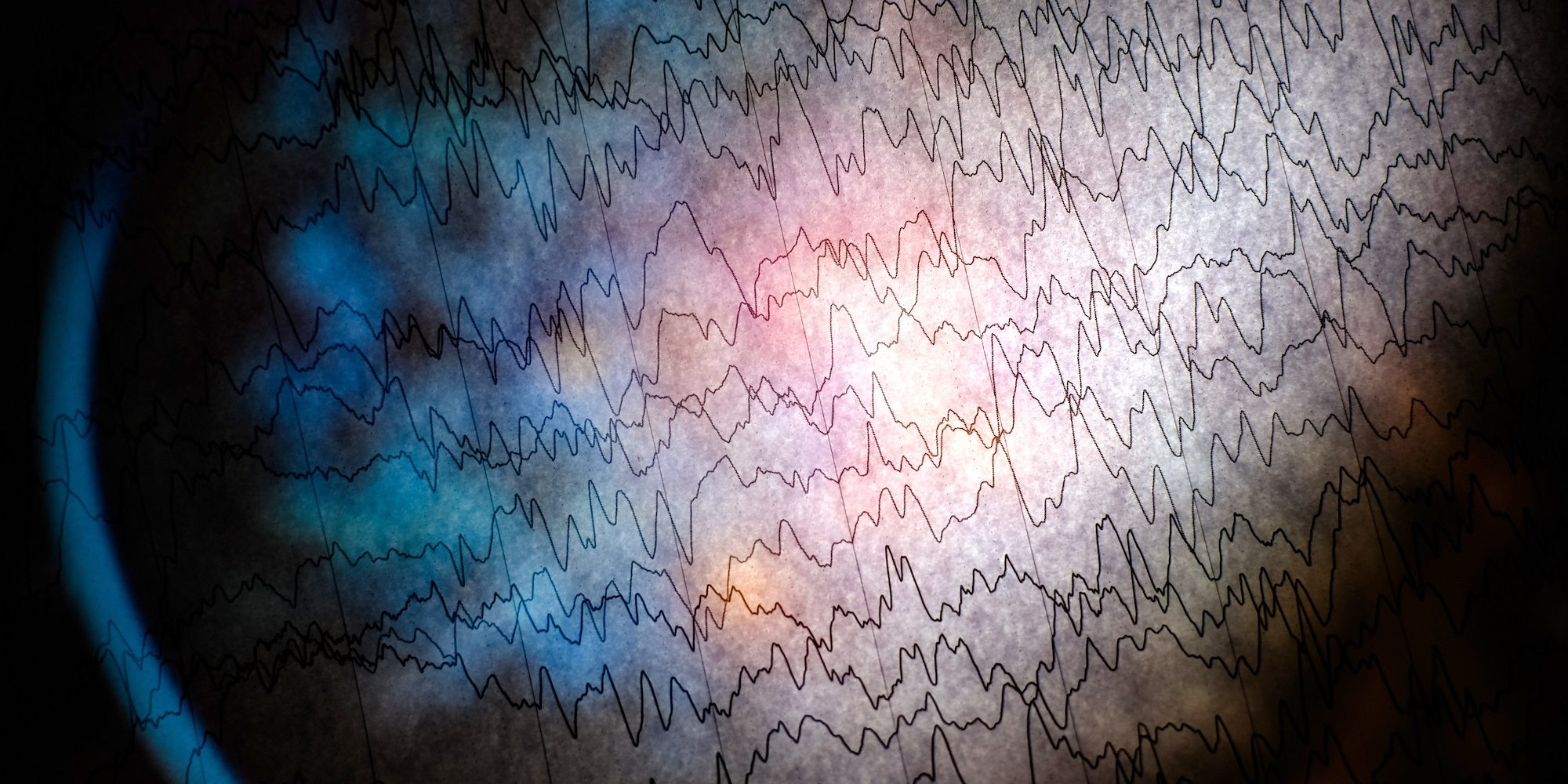

This greater consciousness is not just a metaphysical or regulative ideal: it can be measured. In the growing area of social cognitive neuroscience, cooperative consciousness can be characterized by shared patterns of neural activity.3 Researchers have identified a number of ways of quantifying neural synchronization, which appears to be strongly correlated with phenomenal consciousness. Rather than identifying consciousness with any one neural circuit or part of the brain, it appears to be a function of the synchronic coordination of different parts, such that different kinds of information can be synthesized into a meaningful whole in real time. What makes this really interesting, is that phase alignment appears not only within an individual brain, but between people taking part in joint tasks. That is, when people are asked to perform an activity together, their neural oscillations align. This does not happen when they are merely performing the same task, or similar tasks in the same environment, or competing. Moreover, the higher the degree of cooperation required for the task, the higher the degree of synchronization. And the higher the degree of synchronization, the more the participants experience a felt-sense of connection, sympathy and being ‘in-tune’ with one another.

There is a whole series of pleasurable experiences and activities that share this characteristic as the central feature of what makes them enjoyable: music, dance and marching come to mind immediately, as well as group calisthenics or martial arts training. But any task in which people have to work together, in person and in real time, has this quality as well. The research suggests that there is a neurological foundation to this experience of social connectivity, and that it is the same as the foundation of consciousness itself. If the consciousness of an individual is measurable as the synchronization of different parts of the brain, then whose consciousness are we measuring, when we measure the synchronized oscillations between different brains?

This is all intriguing enough, just in conventional neuroscientific terms. Indeed, now is the time to recall that the technique to measure brainwaves (EEG) was pioneered by someone who was seeking to understand the phenomenon of ‘telepathy.’ Hans Berger believed that the brain sent out and received consciousness via electromagnetic frequencies, just like a radio or telegraph, and later discovered Alpha waves with his new technique. In a funny way, the simplest way to read this data is still quite materialist and reductionist. Only instead of reducing consciousness to brain activity, i.e., meat, we are now reducing consciousness to electromagnetic activity, i.e., light. Brains not only generate such oscillations, they also appear, at the very least, to be affected by the oscillations from other brains, if not the environment more generally. (The next logical step is to ask whether brains are really primarily receivers, capturing and channeling specific frequencies of consciousness-at-large in the universe.) Cooperative consciousness, then, is quantifiable, at least in principle. So what would it look like to treat consciousness itself as the intrinsic good around which morality revolves?

From a practical perspective, the essence of morality is cooperation. No one will disagree, I assume, that cooperation is a pervasive and significant part of human life. The extent to which we trust one another, even strangers, to handle our money and prepare our food, and not drive on the wrong side of the road, is quite astounding. The classical idea of the social contract is meant to explain the overall prospect of this cooperative living, both the costs and the benefits. It is meant to explain why we want to follow certain laws and norms or, at least, why we should do so, even when we would prefer not to. Generally, we are meant to imagine what it would be like if there were no such contract, and what it would be like to live as isolated individuals, truly self-reliant and independent. Then, we imagine what is necessary, what we are required to give up, in order to be able to live in some sort of society. And when the principles of the preconditions for cooperative living are made clear, what does it take to put those principles into action?

Not surprisingly, the principles are basically the rules and practices that we are already familiar with, and refer to, as morality or ethics. Precepts against killing, stealing, breaking contracts or bearing false witness, and so on, create an environment in which people are able to trust one another, or at least not fear one another, enough to get along with the business of a civilized existence. This involves the division of labor and trade, as well as, ultimately, the arts, education and democracy. Modern neuroscience has ways of measuring these benefits as well, by the way. In their work on Dignity Neuroscience, researchers at Brown University4 have argued that what humans need for their individual and collective well-being, as defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, can be grouped into five classes: (1) agency, autonomy and self-determination; (2) freedom from want; (3) freedom from fear; (4) uniqueness; and (5) unconditionality, including protections for vulnerable populations. Each of these sets of needs shows up in distinct neural circuitry as both a characteristic of normal human function and a site of specific deficits or pathology in the cases where people are exposed to privation, abuse, discrimination, violent conflict, and so on.

Now, in the philosophical tradition, the social contract often has a conservative edge to it. There is a sense that the laws as they are are the correct ones, and that any change to the moral status quo could cause degeneration into chaos. It is also quite minimalistic. It does not really result in robust social cooperation, at least by itself. Its goal, apparently, is to create a situation in which such cooperation is possible, but its benefits seem to be practical. The social contract makes it easier to live longer, but does not really explain what it would mean to live better. In its traditional forms, it doesn’t explain, say, what the meaning of life is. The new view of consciousness provides a way to answer the metaethical question about why cooperation is not only an instrumental good, but the intrinsic good. And it has to do with reinterpreting the relation between the individual and the community.

What the findings in social cognitive neuroscience suggest is that there is no intrinsic difference between the way consciousness arises and appears within a single person, and among a group of people. And if consciousness itself is intrinsically good, as affirmed in the mystical tradition, then more consciousness (or bigger consciousness) is better. But from a practical perspective, consciousness can grow and develop in (at least) two different ways: at the level of the individual and at the interpersonal level. The personal development of consciousness is perhaps most familiar to people within the holistic/integral/spiritual-but-not-religious community. Psycho-spiritual practices such as mindfulness, nature-walks, the arts and music, and so on, all serve to integrate and expand one’s consciousness as we normally understand it. The integration of the self (in a broadly Jungian way) is a rare and difficult achievement, especially for those suffering from, e.g., trauma or depression. (Perhaps we never fully ‘achieve’ it, but continually move closer to it.) As well as being an intrinsic good on its own, this intra-personal integration of consciousness is a necessary precondition for social and cooperative consciousness, just like the social and economic preconditions for cooperation described by the social contract.

Finally, cooperative consciousness also requires one last practical piece: a common cause or task. The way in which people coordinate their consciousness is primarily through participating in a well-defined activity or purpose: think of playing music in a group or orchestra, or a church group building houses at Habitat for Humanity. On the largest scale, if humanity as a whole to is to share in a greater consciousness, it can only be by pursuing a goal or ideal that all humans can take up. Josiah Royce5 referred to this as “loyalty to the cause of loyalty itself.” John Dewey6 described this as a regulative ideal in his discussion of a Common Faith, a public commitment to the public good. In the present context, we can say that the minimal social contract justifies the laws and practices that are already in place, but that we have an additional obligation to see that the benefits of the society so formed are expanded to all people, including the poor, prisoners, the ill, the handicapped, refugees, and so on. In other words, our commitment to universal human rights and universal human dignity must be realized through the formation of a truly universal community, in which all people have both the spiritual and the economic opportunity to take part in ever-larger circles of shared consciousness.

We have already begun to develop the tools to establish which kinds of activities, and in what circumstances, give rise to the greatest degree of integral and shared consciousness. To summarize, we have a series of successive dimensions of human development that form an overall trajectory toward greater, more inclusive, more comprehensive consciousness within the human sphere, each of which has empirical neurological expressions: (1) the social and economic conditions that preserve and support human physical and emotional well-being can be specified through Dignity Neuroscience; (2) ongoing spiritual formation and integration are investigated through research into the neuroscience of prayer, meditation and increasingly-mainstream psychedelic therapies;7 (3) local, interpersonal avenues of cooperative activity are being explored in social cognitive neuroscience; (4) a normative culture of building the universal community though actively pursuing human welfare is defined and comprised by the other three areas. This interpretative, even theological, work is being actively pursued by philosophers, theologians, empirical researchers and practitioners from various fields (including the contributors to this website).

The insights of the new Idealism, in tandem with the rapidly expanding pool of data from the neurosciences, provides the basis for an ethical paradigm that is breath-takingly new, and yet also quite ancient. This model of ethics is not just a theory: it’s a research program, arguably the most important one of our lifetimes.

References

- See, e.g., James, William, (1982). The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Kripal, Jeffrey J. (2019). The Flip: Epiphanies of mind and the future of knowledge. New York: Bellevue. doi: 10.1093/nc/niaa010.

- Valencia, Ana Lucia and Tom Froese. (2020). “What binds us? Inter-brain neural synchronization and its implications for theories of human consciousness” in Neuroscience of Consciousness, 6( 1).

- White, Tara L. and Meghan A. Gonsalves. “Dignity Neuroscience: universal rights are rooted in human brain science” in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2021, 1. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14670.

- Royce, Josiah, John K. Roth ed. (1982) The Philosophy of Josiah Royce. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Dewey, John. A Common Faith. (1966) New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Pollan, Michael. (2019) How to Change your Mind: What the new science of psychedelics teaches us about consciousness, dying, addiction, depression, and transcendence. New York: Penguin: 2019

Essentia Foundation communicates, in an accessible but rigorous manner, the latest results in science and philosophy that point to the mental nature of reality. We are committed to strict, academic-level curation of the material we publish.

Recently published

Reading

Essays

Seeing

Videos

Let us build the future of our culture together

Essentia Foundation is a registered non-profit committed to making its content as accessible as possible. Therefore, we depend on contributions from people like you to continue to do our work. There are many ways to contribute.