How Idealism—and Schopenhauer—saved Tolstoy’s life

Reading | Literature

![]() Michael Asher, BA, FRSL | 2022-07-10

Michael Asher, BA, FRSL | 2022-07-10

In the grip of the nihilistic ethos of late 19th-century materialism and Darwinism, Leo Tolstoy contemplated suicide. He would be saved only by finding confirmation, in Schopenhauer’s idealist philosophy, of his own earlier idealist intuitions. Idealism would go on to deeply transform Tolstoy’s life and work, reconnecting him to the simple but profound intuitions of meaning that pervade the lives of peasants. This easy-to-read essay recounts the existential difficulties of a world-famous individual who presaged both our cultural ethos today, and the transformative opportunities offered by modern idealism.

In 1877, only a year after completing his second masterpiece Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy fell into a severe depression—what he later called an arrest of life. It was so profound that, while undressing alone in the evening, he had to first remove a rope from his room in case he was tempted to hang himself. He refused to take a rifle with him on hunting trips so as to avoid sticking the muzzle into his own mouth. Not quite fifty, Tolstoy had led what most would have considered a full, vigorous and creative life. He had spent a decade in the army, serving as a cadet in the crack Russian artillery at Sebastopol in the Crimean war and, as a writer, had become the star of the St Petersburg literati. The owner of a prosperous thousand-acre estate with many serfs and hundreds of horses, he had a beautiful wife and children, and enjoyed the respect of his class—some said he was more revered in Russia than the Tsar.

Suddenly, though, he could not look back on his life without being seized by horror. “I killed people in war,” he wrote. “I summoned others to duels in order to kill them, gambled at cards; I devoured the fruits of the peasants’ labour and punished them; I fornicated and practised deceit. Lying, thieving, promiscuity… drunkenness, violence, murder… there was not a crime I did not commit…” [1] His life as a writer had been even worse, he thought, with its vanity, self-interest and pride. His literary fame was worth nothing. “I would say to myself, ‘Well fine, so you will be more famous than Gogol, Pushkin, Shakespeare, Molière, more famous than all the writers in the world, and so what?’” [2]

His life was meaningless. He had arrived at a moment of existential crisis, likening himself to a man lost in a dark wood, without any inkling of how to find a way out. Instead of merely sitting down under a tree and accepting it, he began to pace back and forth desperately seeking a path, frenziedly looking for a meaning that he felt must be there. [3]

Tolstoy was aware that he was a casualty of the materialism that had largely supplanted religion as the dominant ideology among European elites since mid-century. As Charles Taylor has written, this period saw a sharp rise in what he calls unbelief, not only because many people lost their faith, but also because new parameters of knowledge undermined the certainty of the old religious values. The most obvious changes were in the way people imagined the world they lived in [4]. Science had demonstrated that the universe was much vaster than the cosy cosmos previously envisaged, and the theory of evolution had shown that forms were not fixed, and that the world existed in a perpetual state of change. “With my own self this belief assumed the form it usually takes among the educated men of our time,” Tolstoy confessed. “The belief was expressed in the word progress … I continued to live, professing faith only in progress. Everything is evolving and I am evolving; and the reason why I am evolving together with all the rest will one day be known to me.” [5]

The precariousness of this outlook had first dawned on him a few years earlier at a public guillotining in Paris. As he watched the heads roll, he felt he had just witnessed a crime that no theory of progress could justify. “I knew it was unnecessary and wrong,” he wrote later, “and therefore that judgements on what is good and necessary must not be based on … progress, but on the instincts of my own soul.” [6] The empiricist-materialist paradigm had, he saw, cut people loose from their moorings, without any moral compass or idea of where they were going. “In answering live in conformity with progress,” he wrote, “I was speaking exactly like a person who is in a boat being carried along by wind and waves and who, when asked the most important and vital question, Where should I steer? avoids answering by saying, We are being carried somewhere.” [7]

Almost everyone of Tolstoy’s acquaintance—both inside and outside Russia—was drifting in this same boat: the materialist malaise affected the entire European privileged class. He saw clearly that this was “not life but only a semblance of life, and the conditions of luxury in which we live deprive us of the possibility of understanding life.” [8] In fact, he thought, the upper classes had substituted the pursuit of pleasure for a sense of meaning: they were aware of the mouth of the dragon gaping beneath them but distracted themselves by self-indulgence and conspicuous consumption. Tolstoy referred to this as epicureanism—he felt he could no longer share it. A few people remained truly ignorant of the problem, though it was too late for him to join them and, in any case, such ignorance tended not to last. The only other ways of escape were equally unsatisfactory: either end the agony by killing oneself, or live a life of quiet desperation, knowing it was all pointless but carrying on anyway—a road to existential misery.

For two years, Tolstoy endured the agony, staving off the temptation of suicide, in the “vague awareness that my [negative] ideas were mistaken” [9]. His life became a quest to discover the answer to a fundamental question: Is there any meaning in my life that will not be annihilated by my death? He quickly realized that he would not find a solution in science, since scientific knowledge was based on certain laws of nature that were simply inductions from observations of nature itself. All science could say, he thought, was that “in the infinity of space and the infinity of time infinitely small particles mutate with infinite complexity. When you understand the laws of these mutations you will understand why you live.” [10]

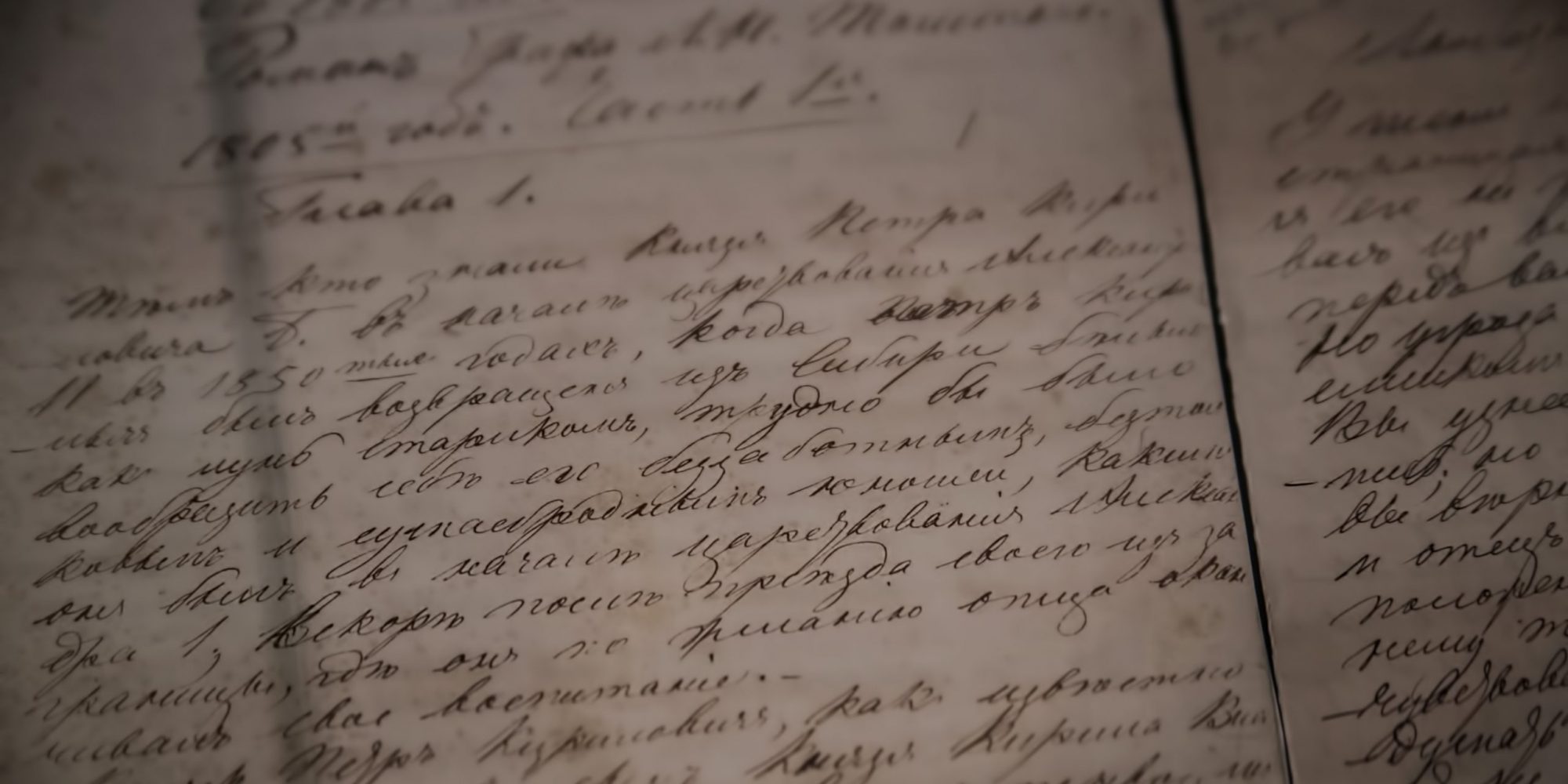

Next he turned to philosophy, and among several philosophers mentioned in the book he wrote about his spiritual crisis—A Confession—is Arthur Schopenhauer. Tolstoy had first read Schopenhauer’s work The World as Will and Representation a decade earlier, while finishing his classic War and Peace, and was delighted with it. “Constant raptures on Schopenhauer,” he wrote to his friend Fet, in 1869, “and a whole series of spiritual delights which I’ve never experienced before … at present I am certain that Schopenhauer is the most brilliant of men” [11]

Tolstoy accepted Schopenhauer’s view that the physical world existed as appearance: what appeared to be objects were no more than representations of a transcendental subject. This subject was will—the essence of the world or the world-in-itself—of which humans were part. “We are not merely the knowing subject,” as Schopenhauer put it, “we ourselves are also among those entities we require to know … we ourselves are the thing-in-itself.” [12] In other words, the universe was mental—a shared mind-at-large—and everything that existed, existed within this universal will.

Even before reading Schopenhauer, Tolstoy had referred to will as the essence of the soul, and in his notoriously revisionist epilogue to War and Peace, he cited will as consciousness or awareness [soznanie], a concept that would later become central to his world view. He observed that man knew himself by consciousness: the awareness of oneself as a being with free will. “To know himself as living, a person must know himself as willing,” he wrote, “he must be conscious of his will. His will, which expresses the essence of his life, a person is conscious of and can only be conscious of as free” [13]. He added that what is discovered in the consciousness of self as a free being is a dimension of reality outside space, time and causality, and that this self is a participant in the divine. “If God is the whole, which contains the infinite universe and I am not just a part of that universe but a participant in the whole … then there is nothing else but this whole, and nothing other than me.” [14]

Clearly, Schopenhauer’s metaphysics was a profound influence on Tolstoy’s writing. Anna Karenina, indeed, has been called, “an artistic embodiment of the world as will and representation.” [15] Other scholars, though, have pointed out that, while the earlier part of War and Peace seems to express a Schopenhauerian perspective, this is problematic, because Tolstoy had not read the World as Will and Representation at the time he wrote it. How is this possible? It seems likely that many of the ideas Tolstoy expressed in this earlier work were his own, and that the reason he so delighted in Schopenhauer’s writing was because he found there the confirmation of intuitions he had had since his younger days. “He had been pondering the same questions,” wrote Sigrid McLaughlin, “and had arrived at similar … conclusions. These ideas were then in all probability reinforced as he gradually became more familiar with Schopenhauer’s philosophy.” [16]

If Schopenhauer’s metaphysics helped Tolstoy find a path out of the dark woods during his spiritual crisis, though, it raises the question as to why this perspective, adopted many years earlier, had not helped him avoid it in the first place. The answer probably lies in the gap between the intellectual or rational grasp of the subject that Tolstoy could apply in his fiction, and the emotional—he termed it irrational—understanding that he could apply in his own person. In fact, as Richard Gustafson has pointed out, in his personal life Tolstoy was in one sense a perpetual outsider. “He had no real friends … and was suspicious of the motives of those close to him. He did not trust or love others easily. He could not bear opposition to his opinions.” [17]

Brought face to face with his imminent annihilation, Tolstoy was obliged to embrace what he agreed with in Schopenhauer’s view in a manner that lay beyond reason. In A Confession, he makes it abundantly clear that he rejects Schopenhauer’s pessimism—the idea, also expressed in various ways by other philosophers and sages, such as Socrates, Solomon and in Buddhism, that life is suffering, and that the will is an unknowable, evil power behind existence.

This was a cultural perspective, he realized: a view from within the culture of the dominant class in civilization. The void of meaning in the lives of Tolstoy’s circle was directly connected with their luxurious lifestyle: a lifestyle legitimized by the Cartesian underpinnings of the Enlightenment. They were parasites who amused themselves at the expense of other people’s labour, and it was almost impossible to feel connected to oneself, others and nature, while living in this manner. Tolstoy asked himself how he could have been so mistaken as to think that his life and the lives of sages such as Solomon, Schopenhauer and others were the true, normal life [18]. After all, Solomon was a king, Buddha a prince, and Schopenhauer the scion of a wealthy banking family—all had been members of the ruling class in their time, and their pronouncements came in reaction to the suffering inherent in hierarchical civilization, where vanity was virtually de rigueur.

What struck Tolstoy most forcibly, indeed, was that the peasants, who formed the majority of the population, were not affected by this joyless ennui. While the upper classes spent their lives in idleness, amusement and dissatisfaction, he observed, and regarded suffering and death as a malicious joke, the peasants “suffer and approach death peacefully and, more often than not, joyfully. … these people who are deprived of all those things, which for the Solomons and I are the only blessings … knew the meaning of life and death, endured suffering and hardship, lived and died and saw this not as vanity but good.” [19]

As he looked more closely at the lives of the illiterate folk, it dawned on him that while they knew nothing of rational learning—science, philosophy, or theology—they trusted in what he termed the irrational: intuition and feeling. In other words, they had faith. Tolstoy saw that it was faith alone that provided them with a sense of meaning.

This faith, Tolstoy observed, was not the same as that extolled by the Orthodox Church: what he referred to as blind faith, or a belief in the infallibility of Church doctrines. He had long since lost his respect for the Church because of its apparent approval of persecution, capital punishment and war. It had, he later wrote, perverted the original Christian message and become a means of controlling the masses. The faith of the ordinary people, he said, was the consciousness of life—the same as Schopenhauer’s will, but without the pessimistic connotations: there was suffering, certainly, but there was also loving kindness. Faith was inseparable from human existence. If there was human life there was faith. If there was none, life was impossible. “Faith remained as irrational to me as before,” he wrote, “but I could not fail to recognize that it alone provides mankind with the answers to the question of life.” [20]

Rational knowledge had led him to the conclusion that life was meaningless: his life had come to a halt and he had wanted to kill himself [21]. The problem was, he now saw, that trying to explain the irrational in terms of reason was the same as attempting to explain the infinite in terms of the finite. His life, of course, had no meaning within time, space and causality, because those were simply aspects of representation, not will. Faith gave meaning to life beyond these limits. “Whatever answers faith gives,” he wrote, “such answers always give an infinite meaning to the finite existence of man; a meaning that is not destroyed by suffering, deprivation or death.” [22] In other words, expecting reason to disclose meaning was like expecting a knife to cut its own handle. Just as the handle directs the knife-blade, so faith—a sense of meaning derived from non-rational values, feelings, and intuitions—gives direction to reason. These feelings are not aspects of representation, but of the transcendent subject: Schopenhauer’s will.

Tolstoy had found his way out of the dark woods: he had the answer to his question. It had been staring him in the face in the work of Schopenhauer over many years, and indeed, had been part of his intuition from childhood, but had been obscured by the dominant ideology of his culture: the Cartesian rationalism that denied feeling. It now required an act of volition to embrace fully. “A great change took place within me,” he wrote, “the roots of which had always been in me. … the life of … the rich and learned, became not only distasteful to me, but lost all meaning.” [23]

Thereafter, he turned his back on his class and refused to indulge any further in the vanities of social distinction. Leaving his wife and children in the mansion he had grown up in, he moved into a small farmhouse on the estate, officially dropped his title, dressed like a peasant, associated with peasants, and worked with his hands alongside them. He disowned his earlier writing, including War and Peace and Anna Karenina, and repudiated the copyrights so as to derive no further income from them. He attempted to make his estate public property, but ran into so much opposition from his wife and family that he dropped the idea.

He continued to write, however, turning out no more epic novels, but penning a large volume of material, starting with the autobiographical A Confession—the story of his spiritual awakening in 1882—followed by other spiritual works, such as What I Believe in 1884. In 1894 he wrote The Kingdom of God is Within You, a work expressing his belief in non-violent resistance that profoundly influenced Gandhi, with whom he corresponded. Among his fiction works was The Death of Ivan Illyich, a novella about an official who, dying as a result of an infection caused by a small accident, realizes that he has wasted his life in pursuit of power, possessions and status, and that he must renounce that life in order to be able to die in peace.

Although a censored edition of Ivan Illyich was published in Russia in 1886, most of Tolstoy’s later works were banned by the authorities and were described as Tolstoy’s abominations by the Orthodox Church, leading to his excommunication. They were published in England though—in Russian as well as in other languages—gaining him fame as a Christian Anarchist and social reformer, both within Russia and worldwide. ‘Tolstoy colonies’ were set up in many countries and his estate became a site of pilgrimage, to which his followers flocked from all over the world. In Russia, those found in possession of his banned works were persecuted, although his global reputation and the reverence in which he was held within his own country prevented the authorities from arresting him. Nevertheless, he remained under police surveillance until his death in 1910.

Although Tolstoy’s reputation as a spiritual leader and social reformer was somewhat eclipsed by the Russian revolution and two world wars, it is now enjoying a renaissance, as it becomes clear that the materialist blight affects not just “a few parasites,” as he put it, but the entire world. Indeed, industrial civilization currently threatens not only the well-being of the Earth, but also the future of the human species itself. Tolstoy was one of the first to grasp that the crisis of our society is not essentially political, economic, or even ecological, but spiritual. As he himself knew intuitively—and perhaps most of us know at some level—it can only be solved by an ontological change, by replacing the narrative of separation we have followed since the Enlightenment with a new non-dualist story: a story of re-connection with the cosmos, the transcendent self.

References

- Tolstoy – A Confession p. 26

- Ibid p. 36

- Ibid p. 51

- Charles Taylor – A Secular Age p. 235

- Tolstoy – A Confession p. 32

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid p. 92

- Ibid p. 63

- Ibid p. 47

- F. Christian – Letters p. 22

- Schopenhauer – The World as Will and Representation

- Gustafson – Resident & Stranger p. 95

- Ibid

- Sigrid McLaughlin – Aspects of Tolstoy’s Intellectual Development p. 207

- Ibid p. 195

- Richard Gustafson – Resident & Stranger – p. 96

- Tolstoy – A Confession p. 68

- Ibid

- Ibid p. 74

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid p. 82

Bibliography

Bartlett, Rosamund – Tolstoy, A Russian Life (2011)

Becker, David – Tolstoy & Schopenhauer & War & Peace – Influence & Ambivalence. Canadian-American Slavic Studies 48 (2014)

Christian R.F. – Tolstoy’s Letters 1828-79 (1978)

Gustafson, Richard – Tolstoy, Resident & Stranger (1986)

Kastrup, Bernardo – Decoding Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics (2020)

McLaughlin, Sigrid – Some Aspects of Tolstoy’s Intellectual Development California Slavic Studies 5 (1970)

Schopenhauer, Arthur – The World as Will & Representation – trans E.J. Payne (1979) Soina O.S. – Leo Tolstoy & the Meaning of Life – Contemporary Search for Ethics –Soviet Studies in Philosophy 25:3 (1986)

Taylor, Charles – A Secular Age (2007)

Thompson, Caleb – Quietism from the Side of Happiness – Tolstoy & Schopenhauer, War & Peace Symposium (2009)

Tolstoy, Leo – A Confession & Other Religious Writings trans Jayne Kentish 1987 (2009)

Essentia Foundation communicates, in an accessible but rigorous manner, the latest results in science and philosophy that point to the mental nature of reality. We are committed to strict, academic-level curation of the material we publish.

Recently published

Reading

Essays

Seeing

Videos

Let us build the future of our culture together

Essentia Foundation is a registered non-profit committed to making its content as accessible as possible. Therefore, we depend on contributions from people like you to continue to do our work. There are many ways to contribute.